Making films in India is hard not because of the heat, or the bureaucracy, or the traffic. Not even, says Liz Mermin, the director of Bollywood underworld exposé Shot in Bombay, because its superstar subject Sanjay Dutt grew nervous about the project. "The hardest thing for a film-maker is that you fly there, look around, take out your camera – and everything is a cliche. Poverty, chaos, cows, flowers: I was going around desperately looking for a shot I hadn't seen before."

That difficulty – to say nothing of the challenge of depicting India in more than just western terms – led Louis Malle to name the first section of his six-hour Phantom India (1969) "The Impossible Camera". Yet, even though "India" in its teeming multiplicity may be as much a conceit as "the west", many directors have stepped up to this challenge. Jean Renoir's The River (1951), Roberto Rossellini's India: Matri Bhumi (1959), Fritz Lang's The Tiger of Eschnapur (1959), Pier Paolo Pasolini's Notes For A Film On India (1967), Werner Herzog's Jag Mandir (1991), and, yes, Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire (2008) are just a fraction of the films that have sought to make their outsider perspectives a virtue.

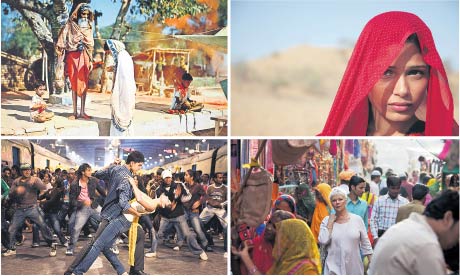

Now joining that list are John Madden's The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel and Michael Winterbottom's Trishna. The former, an adaptation of Deborah Moggach's 2004 novel These Foolish Things, follows a group of English pensioners (Judi Dench, Maggie Smith, Bill Nighy and Penelope Wilton) as they travel to a retirement sanctuary in Jaipur that, although more decrepit than either the brochure or its manager (Dev Patel) let on, proves to be a much-loved base for them as they go about re-envisaging and rebuilding their lives.

Trishna, meanwhile, is the latest instalment in Winterbottom's ongoing dedication to bringing the novels of Thomas Hardy to the big screen. Following Jude (1996) and The Claim (2000), his version of The Mayor of Casterbridge, he has relocated Tess of the d'Urbervilles to modern-day India. In the title role, Freida Pinto plays a smalltown girl who, after her father has an accident, goes to work for a rich British businessman (Riz Ahmed) with whom she falls in love. They move, first to a turbulent Mumbai, later to palatial Rajasthan where he runs a hotel, but over time their relationship fractures and darkens.

In some ways, these films are poles apart. Madden, best known as the director of Shakespeare In Love, describes The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel as "a comedy of dislocation" that "evokes the form of a William Shakespeare comedy whose characters are transplanted to a different environment". Ol Parker's screenplay is informed by politics – its starting point is the outsourcing of old age, a phenomenon promoted by Indian finance minister Jaswant Singh in 2003 when he pushed for the nation to become a "global health destination" – but certainly not defined by it.

By contrast, Trishna is a tragedy marked by improvised acting, cityscapes full of MTV-style billboards, yuppie bars and dance studios, and, in no small part due to Marcel Zyskind's atmospheric, hand-held photography, a persistent mood of ellipsis and in-betweenness. Winterbottom is more attuned to the social and economic niceties of his characters: "In the novel, Tess's family is one of the poorest in the village," he says. "In Trishna they're the equivalent of a lower middle-class family. They aspire to benefit from the changes but find themselves in a situation that's difficult with the growing economy, urbanisation and changing values."

Yet it's precisely this fascination with India as a place in flux that the two films have in common. Historically, outsider artists have tended to portray the nation as old, spiritual, rural, in thrall to tradition. For some, this was its appeal, for others, a curse. In Dick Fontaine's Temporary Person Passing Through (1965), a melancholic James Cameron (the veteran journalist, not the director) laments: "There's too much of everything, too many people, too many cows, too many problems. Too much India, really."

Now, in 2012, when Indian politicians are increasingly embracing neoliberalism and boasting of the country's Bric status, it's more likely to be depicted as a modern, urban, entrepreneur-friendly tiger economy. The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel relocates Moggach's novel from IT hub Bangalore to more picturesque Jaipur, but still shows an India that's the dynamic antithesis to – even the cure for – a Britain defined by failed internet ventures, hip-operation waiting lists and cramped bungalow homes. "Transformation is at its heart," argues Parker.

For Winterbottom, whose In This World and Code 46 showcased his appreciation of the cultural dynamics and faultlines that animate contemporary globalisation, the transformations in India serve to cast a cruel spotlight on Britain. "Hardy's novels are often about modernity and speed and energy. But it's hard to get that sense of a dynamically changing world if you set one in this country. Here the problems are more to do with a lack of mobility rather than an excess of it."

Is there a danger that this fascination with the turbo-economics of the east becomes a new kind of orientalism, one in its own way as romanticising as Eat Pray Love's ascription of superior wisdom to India? Ashim Ahluwalia, Mumbai-based director of John and Jane (2005), a brilliantly disturbing drama-documentary mashup about urban identity in modern India, believes it is: "In order to understand with any depth what it means to be Indian today, we should stop endorsing the collective fantasy of 'India Shining' – this laughable state of mind in which many modern Indians imagine a new incredible India that looks and feels like a first-world nation."

Anjalika Sagar, one half of the Otolith Group, whose films explore radical and utopian flashpoints since the war, says: "India is proud of its film industry and its tourist industry. Often these are the same thing. The country's history, nature and air are under threat. Mining companies are setting its agenda. Millions of people are being displaced. How can you make a film about the country without engaging with its socio-political underclass?"

Sagar looks back on the 80s with a touch of nostalgia. Although films and TV series such as Gandhi, The Far Pavilions and The Jewel In The Crown were sometimes accused of stoking a Raj revival, a foretaste of what writer Pankaj Mishra has dubbed the "neo-imperialist vision" of Niall Ferguson and other evangelists for the empire, she defends them for "at least engaging with questions of power. Independence wasn't so far in the past back then. Now, with a tiny number of exceptions, there's no attention to the history of colonialism. There's an amnesia within India."

If that's true, it might represent an opportunity for British directors and screenwriters – though they shouldn't assume that taking it will guarantee them either audiences or appreciation. "In the big cities especially there's often a real fuck-off attitude towards the west," laughs Mermin. "There's not a trace of cultural insecurity that a particular postcolonial sensibility might wish to see."

Ahluwalia puts it another way: "We've always been eating brains in Indiana Jones films or stammering awkward English sentences in various other western productions, so I don't think we have high expectations."

The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel is released on 24 February; Trishna on 9 March